US Authorities Buy American Surveillance Data: Explained in 2025

- Table of Contents

- Do US Authorities Buy American Surveillance Data?

- Do Any US Laws Protect Personal Data?

- Are Other Governments Purchasing Americans’ Commercially Available Data?

- Can National Intelligence Agencies Spy Without a Warrant?

- How to Protect Your Civil Liberties

- Final Thoughts: The Sale of US Citizens’ Data

- FAQ

Quick Summary: U.S. Government Buying Surveillance Data

Agencies in the American government can buy sensitive personal information from data brokers without needing a warrant.

To protect yourself, use a data removal service, like Incogni, and a virtual private network, like NordVPN.

The intelligence community in the United States has long made it clear that it will prioritize gathering information over civil liberties anytime the two conflict. With millions of personal data records available via data brokers, it’s no surprise the government has come buying. Today, I’ll explain how U.S. authorities buy American surveillance data — and how you can better protect your information.

Ever since Edward Snowden blew the whistle on the massive warrantless surveillance program called PRISM by the U.S. National Security Agency (NSA), we’ve known just how little the federal government values Americans’ privacy. Plus, U.S. intelligence agencies — including the CIA, DIA, FBI, NGA and NSA — have used the Five Eyes agreement as a constitutional loophole since at least World War II.

But now they’ve got a new loophole: Data brokers, which make money by aggregating and selling personal information, don’t need warrants to gather that data. If intelligence agencies buy information from them, they can circumvent warrant requirements and collect private data that should be protected by the Fourth Amendment.

It’s a stark picture, but luckily, Americans aren’t helpless. If data brokers and intelligence agencies don’t need permission to spy on you, you don’t need permission to fight back — and today, I’ll show you exactly how.

Do US Authorities Buy American Surveillance Data?

Yes, they do. A wide range of intelligence agencies have been revealed to buy personal information from data brokers, including the Internal Revenue Service (IRS), the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI), the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) and the Department of Defense (DOD).

This bombshell information comes from a report by the Office of the Director of National Intelligence (ODNI), another U.S. agency that acts as a watchdog for the intelligence community. The report, commissioned in late 2021 and only declassified in June 2023, goes into detail on the intelligence uses of “commercially available information” (CAI).

What Is Commercially Available Information (CAI)?

According to the report, CAI (also sometimes called “commercially available data”) is any information that can be purchased from another party. This makes it distinct from stolen or leaked information, as well as the kind of intelligence gathered through PRISM, which was obtained for free through backdoors installed in communication networks.

In other words, commercially available data is out there for anyone — and the government just happens to be buying. So, if it’s a product being freely bought and sold, what’s the problem? Well, nothing, if you consented to release your information to the data brokers. However, chances are extremely good that you did no such thing.

Do Any US Laws Protect Personal Data?

As you can read in my summary of U.S. online privacy laws, the Land of the Free has no comprehensive law protecting consumer data. There are patchwork protections, but a massive amount of data can fall through the cracks. The prevalence of big-tech data collection shows you just how much of your personal information can be harvested legally.

On top of that, there are plenty of laws, like the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act (FISA), that give the United States government a blank check to expand its surveillance capabilities.

The exact data gathered can include your contact information, geolocation tracking, political affiliations, online activity and more. The ODNI report clearly states that this data “can be misused to pry into private lives, ruin reputations, and cause emotional distress and threaten the safety of individuals.”

What Are Data Brokers?

The ODNI report proves the U.S. government is buying sensitive data on civilians and stockpiling it into profiles. However, it’s not shady hackers on the dark web that are selling that sensitive information to them — it’s data brokers, which are technically legal.

The ODNI report quotes an earlier report from 2013, which describes how data brokers “maintain large, sophisticated databases…that can include credit histories, insurance claims, criminal records, employment histories, incomes, ethnicities, purchase histories, and interests.” Brokers make a fortune selling access to these records.

Information Collected by Data Brokers

Some of the information in brokers’ databases is a matter of public record, but profiles also include non-public information. This is often purchased directly from the source, such as credit history from a credit bureau or internet browsing history from an internet service provider (ISP).

Then there’s information you give up without knowing about it. Many apps collect information in the background and make most of their money selling it — like how Facebook turns a profit with a product that appears to be free.

The bottom line is that if you think data brokers don’t have your information, you’re wrong. I ran a basic scan with Incogni and discovered my identity on no fewer than 101 brokerage sites, and I’m someone who pays attention to this stuff for a living.

Are Other Governments Purchasing Americans’ Commercially Available Data?

It’s worth recognizing that if the U.S. government agencies can legally purchase and use this collected personal data of Americans, other countries would have the same opportunity.

Congress and government agencies have expressed deep concerns in recent years that China can collect and track U.S. personal data about citizens via the social media app Tiktok; there should be just as much concern about foreign adversaries purchasing commercially available data about Americans via data brokers.

This national security threat has led to a bipartisan bill proposal: The Protecting Americans’ Data from Foreign Surveillance Act of 2023. However, the bill focuses on a foreign government’s ability to gather this data, and does not address the U.S. government’s use of the same techniques.

Can National Intelligence Agencies Spy Without a Warrant?

Let’s summarize what we know so far. Data brokers compile public and private information into massive profiles on individuals, most of whom never knowingly consented to release that information. Government agencies — both foreign and domestic — then purchase that information, acquiring intelligence they would normally need a warrant for.

So, why doesn’t the Fourth Amendment protect Americans? The Bill of Rights holds that no American can be deprived of their right to privacy without due process — specifically, a search warrant issued by a court of law. This prevents law enforcement from grabbing your cell phone records or credit history directly.

However, as the ODNI report notes, the Fourth Amendment does not protect public information. This even applies if you didn’t know or understand that you were agreeing to make the information public. So, for example, the victims in the case of Muslim Pro, the app that built a database on innocent American Muslims, have no constitutional recourse.

This is already having profound effects in reality. In 2021, when the ODNI report was first commissioned, documents had already revealed that Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) was buying cell phone location records and using them to target migrants, the vast majority of whom had committed no crimes.

How to Protect Your Civil Liberties

Now that I’ve laid out all the frightening details, it’s time to talk about how you can turn the tables. It would take an act of Congress to close the data broker loophole for good, but until then, you’re far from powerless.

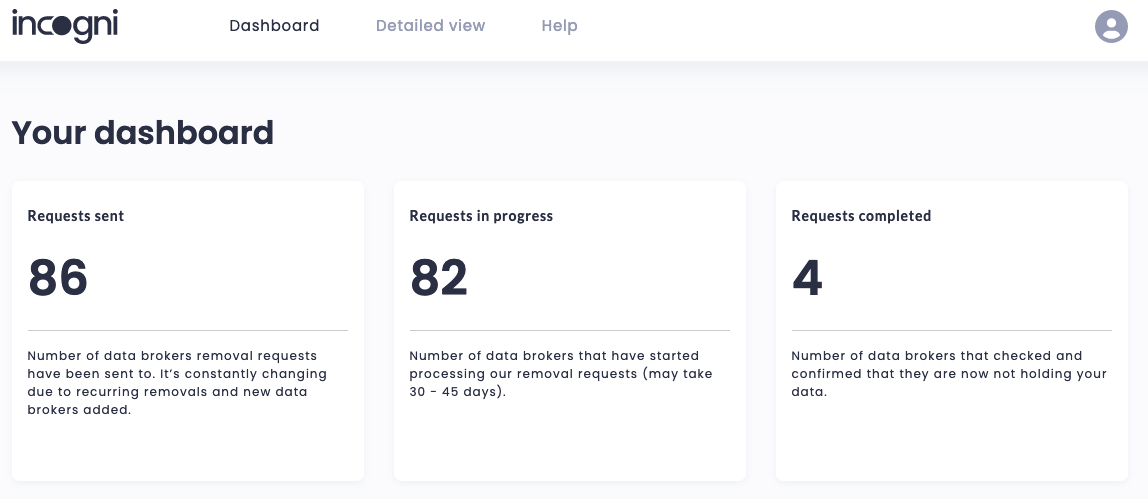

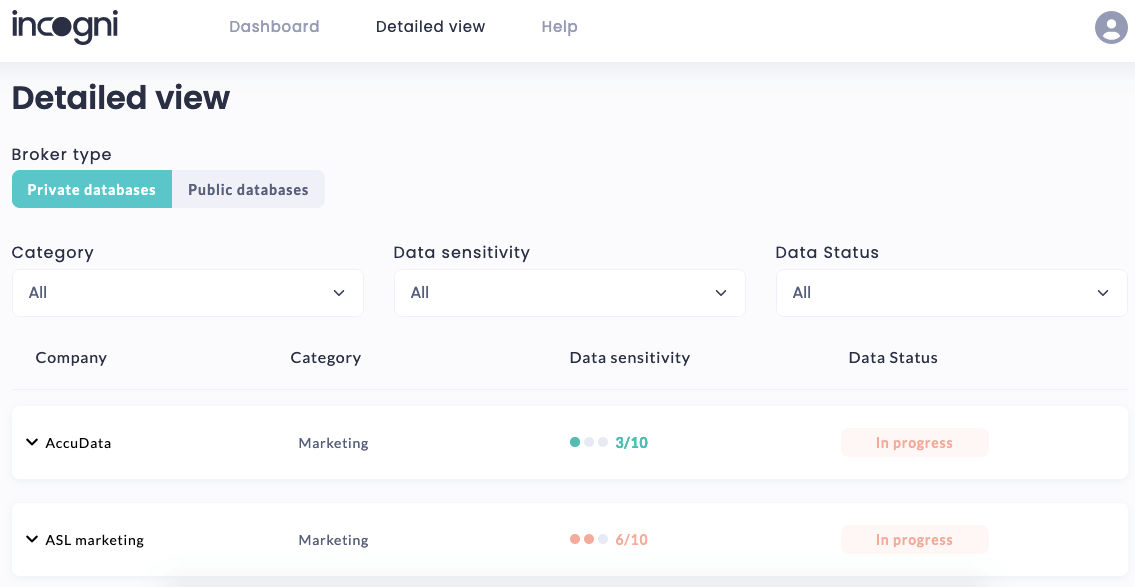

Use a Data Removal App

A few apps have already sprung up in response to the privacy risk posed by data brokers. One of the best is Surfshark’s Incogni, which I recently wrote up in a full Incogni review. Other apps include IDX ForgetMe, OneRep and Abine’s DeleteMe, though I’d argue that Incogni has the best privacy protections.

In order to comply with privacy laws like the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) in the EU, data brokers may have to delete your data if you specifically request it. Data removal apps automate the process of finding which data brokers have information on you, sending deletion requests and monitoring the databases for compliance.

The apps have different ways of going about this. Most of them actually search for your information on data brokers, but Incogni instead uses an algorithm to determine where your information might be. This helps it work faster, if less accurately.

Data removal apps are a great first step to mitigate your unwanted online presence, but they come with some tradeoffs. For an app to find your information, you have to share a lot of it first, including your home address and social security number. There’s also limited recourse if a data broker refuses a removal request. Still, I recommend giving one a shot — it can only help.

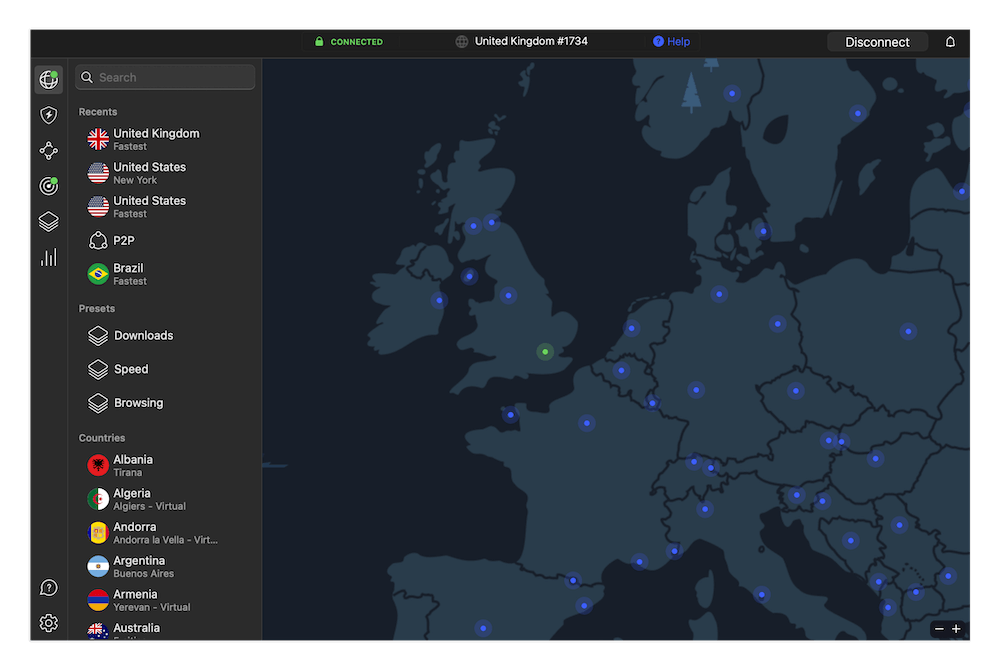

Use a VPN

A virtual private network (VPN) is an app that lets you connect to a server and browse the internet using that server’s identity instead of your own. Your connection to the server is encrypted, making it impossible to connect your identity to your activity — in other words, VPNs help you achieve true online anonymity.

The benefits of a VPN are often misinterpreted. Using one doesn’t make you impervious to leaking your information. You can still lose your information if you give it up freely to unscrupulous websites or social engineering attacks. However, a VPN will make it a lot harder for your internet service provider (or other companies using tracking technology) to establish and sell an information trail to data brokers.

My favorite VPN is NordVPN; check out my full NordVPN review to learn why. In short, it’s fast, secure and cheap. If it’s not for you, though, visit the ExpressVPN review page for a strong alternative at a more expensive price.

Practice Personal Cybersecurity

The basics of personal cybersecurity are no different from being intelligent about anything you want to protect. You wouldn’t hand your phone or valuable jewelry off to a stranger just because they asked for it, so why would you give up your SSN just because the person asking is on the other side of an internet connection?

Never download an app without looking it up in the news, reading a cross-section of reviews and going over the user agreement as closely as you can. Be extremely careful about sharing any information on social media. Whenever a website asks for your personal data, look at its privacy policy to see whether it’s safe — sites are legally required to post that info.

It’s also a good idea to use browsers known to be secure, such as Firefox and Brave. These browsers block cookies and ads automatically, interfering with the trackers often used to harvest and sell your data. You can also periodically delete cookies from your browser. (There are some browsers with built-in VPNs, as well.)

Push for Political Change

Of course, individual solutions like the ones above can only take us so far. The only real way to curb the U.S. intelligence apparatus’s appetite for sensitive personal information is to push Congress and the White House to regulate data brokers more closely.

Data privacy is a surprisingly bipartisan issue, so with a public groundswell, legislation actually has a chance. The FTC has even filed a lawsuit against the data broker Kochava for allegedly selling geolocation data from hundreds of millions of mobile devices — I wouldn’t be surprised if big cases like this end up in front of the Supreme Court soon.

Write your representatives and tell them you strongly support a law to prevent data brokers from obtaining any information without consent. The ultimate goal is a federal answer to the privacy laws already enacted in California and other states.

Final Thoughts: The Sale of US Citizens’ Data

The U.S. government using data brokers to circumvent warrant requirements is bad news, but not unexpected. This scheme is really just another variation on what they’ve been doing with Five Eyes for decades.

The usual remedies apply: protect your data with common sense and a VPN while pushing for political change. Test NordVPN’s capabilities with a month-long return option, and secure long-term plans at reduced prices.

What are your thoughts on the ODNI report? Do you have any other tips for keeping your information out of data brokers’ hands? Let’s talk about it in the comments. Thanks for reading!

FAQ

Does the US Buy Data?

Yes. According to a report from the Office of the Director of National Intelligence, multiple U.S. government agencies have bought data from brokerage services, building profiles on U.S. citizens who have not been charged with any crime.Does the Government Collect Your Data?

The government has several ways of collecting data without obtaining a search warrant. In addition to monitoring communications through programs like PRISM, it can also buy info from data brokers, since that data is technically public.What Agency Monitors the Internet?

Agencies known to have made deals with data brokers for sensitive and intimate information include the IRS, the FBI, the Department of Defense and the Department of Homeland Security, especially ICE and CBP.

Leave a Reply